Zone and Climate Awareness

Mast orchards represent a very effective means for modern land stewards to improve habitat and increase available nutrition for wildlife on their property. However, different tree and shrub species are adapted to different climates. It’s important to select species best suited to the local climate, including the macro and microclimates, to maximize growth and mast production.

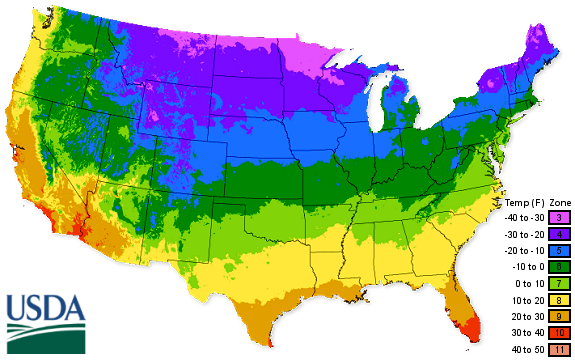

First, determine the macroclimate – a characterization of average annual temperatures and rainfall. This is quickly done by consulting the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map. The Plant Hardiness Map, the standard by which gardeners and growers determine which plants are most likely to thrive at a specific location, divides the nation into 10-degree F zones based on average annual minimum winter temperatures. These zones, or regions, are then used to describe the range in which plants are adapted and can be grown.

Chestnut Hill Outdoors lists these zones for each product to ensure you pick the right plants for your region. From North to South – Dark Purple is Zone 4, Blue Zone 5, Dark Green is Zone 6, Pale Green is Zone 7, Yellow is Zone 8, and Tan is Zone 9. They also check all orders to ensure plant species are appropriately suited to their destinations.

Once the list of potential plants is prepared, it’s time to go from the extensive to the intensive and look at where certain species might be suited on an individual property. Depending on the particular property, there can be considerable variation in elevation, slope, aspect, and proximity to bodies of water, all of which can create greater temperature variations at a specific site. These so-called micro-climates can enhance or hinder the growth rates of particular plants and should be considered when choosing tree species for a particular location.

Some areas can be quickly ruled out. As a general rule of thumb, it’s best to avoid low-lying frost pockets or areas that stay wet in the spring for extended periods during snow melt. This is especially true for mast trees that break dormancy early and could be damaged by late-season frosts that settle into frost pockets at the bottom of valleys or even swales.

Other areas might be ideal. Gently sloping hillsides will provide a warmer microclimate, where cold air drains off. This is especially true for slopes with a southern aspect that receives more direct sunlight and less cold wind – a common planting requirement for many mast-producing species.

Sub-optimum sites may still offer some possibilities. Tree species adapted to cooler hardiness zones or macroclimates might still be productive in lower areas or those exposed to northerly winds. Some species, like swamp white oak, do better in moist soils. It’s also important to remember that these variations typically occur on a gradient rather than an abrupt change. Tree and shrub species with a broader range of tolerance to temperature and shade can be used along the margins of microclimate changes.

Left: Sheng Persimmon, drops fruit in early-mid fall. Right: Everbearing Mulberry, drops fruit in late spring.

Planting a variety of hard and soft mast species offers several advantages. The obvious one is providing more and different food over a more extended period. Another is providing a hedge against annual climatic fluctuations. In a dry year, brambles like raspberries and blackberries may not be as productive, but other soft-mast producers like mulberries, plums, and persimmons may still produce fruit. Variety also allows more options for site-specific species selection. Many landowners pick out the species they want to plant and then decide where they’re best suited. An alternate approach might be to map out the microclimates, then determine which species are best suited to specific locations.